So often, we celebrate the faces of entertainment: the actors, actresses, models, musicians. Our attraction to celebrities embeds us in their livelihood, causing people to live vicariously through the names that populate magazines, tabloids, TV. These faces represents an escape—hope for some. For a fleeting juncture, they allow us to pause our pedestrian existence, and resume life according to superficial grandeur. If only for a moment, we can transcend normalcy.

Too often, however, we romanticize the idea of fame and success to a delusional point, forgetting that these individuals achieved their respective statuses with a resolute work ethic, and supportive, necessary teams. In music, those support systems typically exist in the studio—mainly, the audio engineers. They’re the ones who ensure the music’s flawless acoustics and transitions; their meticulousness dictates a project’s potential. When artists find not only a reliable audio engineer, but one who can interpret their artistic vision, learn their habits, and go beyond the job description, they lock them down.

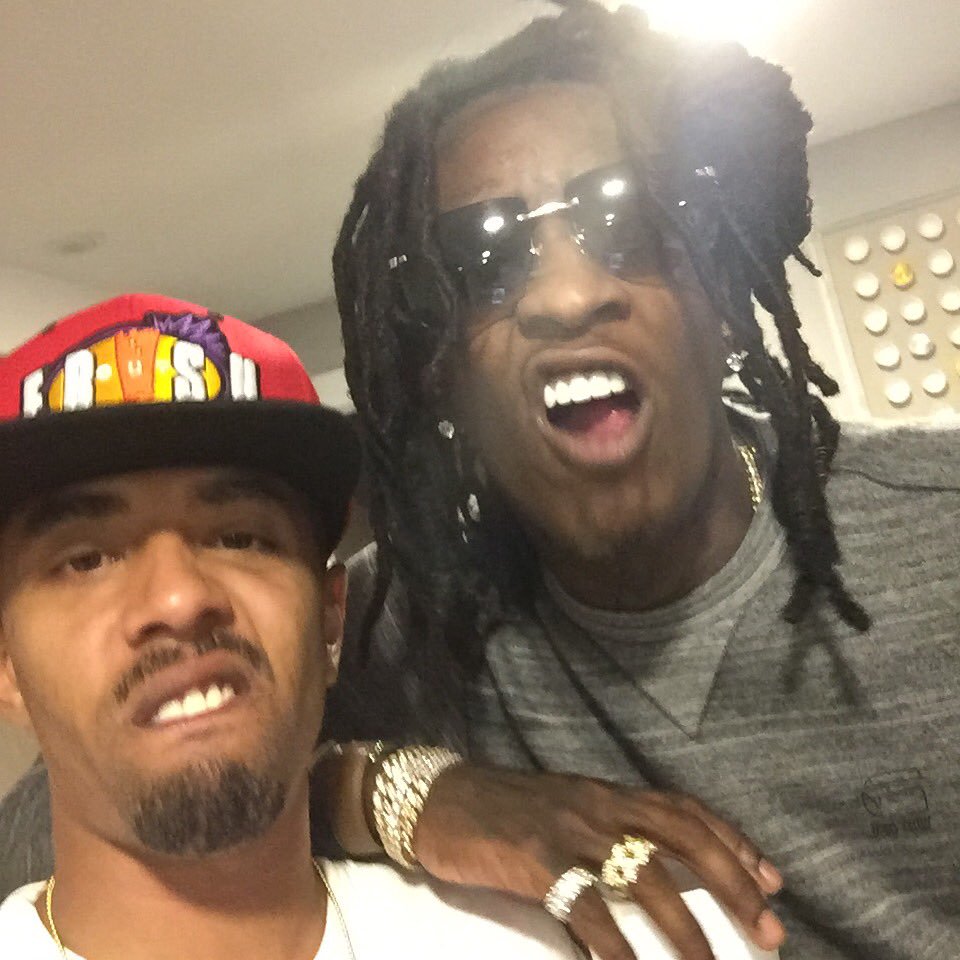

Atlanta’s Sean Paine has developed into one of Hip Hop’s premiere audio engineers. His technical prowess has helped some of the industry’s biggest names, from Young Thug to Future, and 2 Chainz to Lil Wayne. Through a tenacious hustle fueled by an unwavering passion, Sean continuously proves his value, which hinges upon a deep musical knowledge and an outside-the-box mentality. These intangibles help Sean ensure pristine sound quality for rap’s developing and highly-established talent. Arguably his biggest, most consistent client—and the one who aided Sean’s ascension—is sitting in Hip Hop’s driver seat with a license plate that reads “TRAP GOD”. To us, he’s immortalized as Gucci Mane. To Sean, he’s just Radric Davis—his partner, collaborator, and most importantly, friend.

During Gucci’s palpable three-year absence, we managed to “miraculously” receive new Wop projects—frequently. A conceivably impossible task was carried out by hundreds of pre-prison recorded verses, persistent outreach, willing collaborators, and hungry fans. It was all brought to fruition by Sean Paine, Gucci’s connection to the outside world. Wop might’ve officially been released in late May ’16, but thanks to Sean, we were never deprived of hearing his voice. Sean’s necessary outside-the-box mentality kept Gucci in the limelight while Wop suffered some of his darkest times. A musical Swiss Army Knife, Sean’s utility isn’t just anchored to engineering.

After some back and forth, Sean and I were able to catch up on the phone to discuss his intriguing background, stories with Gucci, work with other famous rappers, and his own music career. Sean might be known for helping Wizop, but his identity isn’t characterized by that—it’s just part of his story. Read below to learn more about one of Hip Hop’s hardest working individuals.

Hey Sean, what’s up man this is Zach from ZeusWolf. Is this still a good time to talk?

Hey, what’s going on? I’m actually about to record Gucci right now, can you call me in about an hour?

One-hour later

How’d the recording session go?

It went well. We’re working on Drop Top Wizop. I can’t say too much information about it though.

Totally understand. Let’s get into your background. If being a music engineer didn’t work out for you, what kind of work would you have pursued?

Definitely investment banking and real estate. I received a major in business finance and economics from Morehouse college, so that was my passion. I’m actually getting back into it, and studying for my GMAT currently so I can go back and get my MBA.

So you’re trying to expand beyond just audio engineering?

Definitely. I’m trying to come out with a set of plugins for engineering, and I’m always going to be an artist—you know, rap and make beats. But I’m really trying to build my brand when it comes to engineering. So I’m going to get involved in more tutorials, and I’m actually going to start a learning session because I get flown out to Canada once or twice a year to share my experience with the students. I also get flown to other schools to tell them about myself, but they really want to learn about the specifics behind engineering. I definitely like teaching though. I used to be an associate teacher for like four or five years when I was at Morehouse.

How did you initially get into audio engineering?

Well like I said I studied business finance and economics at Morehouse, and then I went to Full Sail after that for eight-months to get my audio engineering degree. Then I started interning at Patchwerk [Atlanta-based recording studio] through my bro Corey who was Gucci’s engineer at the time. And then from there, I started sitting in on sessions and learning how to actually work with industry people. After that Gucci started taking a liking to me, and now we’re at where we’re at now.

When you were at Morehouse what made you realize that you wanted to change course and pursue audio engineering as opposed to investment banking and real estate?

It wasn’t really like that. I graduated at the top of my class at Morehouse—I was supposed to graduate in three-years but I got caught up in some bull crap, so—I just kind of let it bundle out, an I never really went for the corporate route. I always loved music, and I was always doing music anyway, so my brother told me that knows Corey from Patchwerk. Corey and my brother both went to Morehouse, and he was telling me that Corey could plug me in. My brother really convinced me to go to school for engineering. I actually wanted to be a rapper—that’s how I started. I’m a decent rapper and I wasn’t even thinking about engineering.

Out of rapping, producing, and engineering, what’s your favorite thing to do?

I like to rap. I honestly like to rap and produce the whole song by myself. I make the beat, I rap on it—that’s what I enjoy. It’s just my vision entirely.

You put out the Good and Bad mixtape a couple of years back. Was that your first project?

Yeah. That’s the one with Riff Raff, Lil B, Bankroll Fresh. But, I have a new album coming out: Sean Paine, it’s self-titled.

What can we expect from Sean Paine?

THAT motha’fucka, alright. Waaaay better than Good and Bad. That was just some shit I was pulling together, because Wop always said we bros for life—good or bad. So I was just like yeah, alright I’m gonna put a tape out called Good and Bad. The new tape has features from Trinidad James, Yung Lean. Then I’m going to try and get Fred Durst on it [vocalist for Limp Bizkit]. Hm, who else? Loso Loaded. That’s my boy, I knew him before he was Loso when he was just trigga. Then we also have Rich Boy and OJ da Juiceman. My new project is dope, and I’m producing all the beats on it, which makes it better.

Was Good and Bad just you messing around? You think this new project is going to be the real rap introduction to you?

Yeah, honestly I was mixing all those Gucci songs, and I kind of just got bored. So I would just mix all of his stuff, and then I was just sitting around thinking about what to do. Sometimes I would just put a little mic on, and just rap and shit. I started meeting all of these people, and just asked them to get on songs. So it wasn’t like “oh this is a hit”; I was just putting shit together, to be honest with you. I really wish I would’ve taken my time with it. That’s why I’m taking my time with this next one because I want it to be good. I just started working on it about two-months ago. Don’t get it twisted—I’ve got a whole bunch of songs recorded. But I just, I don’t know. I don’t want to just put them out. I want to make an impact, I don’t want to just be putting shit out for no reason. I want to make money.

When you were at Patchwerk you started linking up with Gucci. Looking back, can you pinpoint one or two moments that made the difference from being just some guy who worked with Gucci to becoming his engineer and right-hand man?

I mean, shit. He just took a liking to me. I would go above and beyond my duties of an engineer—I would do more that just that. My grandpa always taught me there’s always a way to do something better. You know, they might make a car, but there’s always a way to make a better car. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel, but it’s always good to go above and beyond your expectations and you’ll get recognized. That’s what my grandfather said to me.

How did you go above and beyond for Gucci?

Shit, he just asked me to do stuff and I just did it. I didn’t even think twice, I just did it. I didn’t think about the money, I just thought about the dream. I wasn’t money hungry or anything like that. I was humble, very humble, and just let it come to me instead of just chasing it. But I was always on point. I would always try to be quick and efficient. Him being locked up though, and throwing everything on me, trusting me with that stuff [constructing his in-prison releases]—I think that might have been the main factor. But even before that, me and him left Patchwerk and started our own studio called Brick Factory in East Atlanta, and I was the head engineer there. That’s where I mixed all the Thug records; the Migos were there, Peewee [Longway], everybody basically.

When he went away, you were responsible for taking his pre-prison recorded verses and mixing them with verses over the phone. So were you essentially crafting the projects through your own vision?

Sort of, sometimes he would do it. Because a lot of those songs were already completed. At first, we were able to talk on the phone. At first, he was orchestrating. He would call me and I would play all the songs that he got. And then he would just try and come up with a track list. As time progressed, we were unable to communicate on the phone so we could only talk via email, so he’d just ask me, “Is it hard?” Then he’d ask me for the track list, so I’d send him that. Then as time progressed even further, some of the songs were incomplete. So I thought, okay let me try and do what Gucci would do, and just work with everybody. I just started reaching out to all types of different artists for features and stuff like that to complete the projects. My thought process was, “Okay, let me try and tap into their followings as well.” That was the whole purpose behind it—I was trying to make him as big as possible, so when he got out he’d be even bigger. I’d reach out to anyone, you know—Project Pat. A lot of people who Gucci rocked with, I’d reach out to them first. Towards the end, he just let me do it. He said, “Put it together. I trust you.”

Did you feel pressure with being his connection to the outside world?

Nah, I was actually enjoying it. I didn’t feel pressure, I just felt like I couldn’t put out any whack shit. I’ve got to make sure it’s hot. Towards the end when we exhausted the hard drive, and I said, “Wop you need to let them wait on you to get out.” I had put out a project about every two months before he got out. And he would say, “Put another one out.” But I didn’t want to do that. I didn’t want to water down the music.

How many verses did he have recorded before he went away?

Shit, man so many I don’t even know. Hundreds. But sometimes, the beats would be outdated so I would reach out to producers and ask them to remake it. Like C Note, he remade The Spot Soundtrack. I wanted the producers to make the beats more modern, more hot. A lot of people turned their backs on Gucci and I didn’t—that’s my boy. Everybody goes through stuff, but that doesn’t matter. It’s all about how you come out of it.

Is it fun being back in the studio together?

Hell yeah, man. That’s all it was about. The whole time he was locked up and I was putting that music out, it wasn’t fun for me. I couldn’t enjoy it. You know, I put it out, but my boy’s locked up. The fans might love it and all that, but I’m like my boy can’t even see this shit. That ain’t what I got into this shit for.

I’ve heard Gucci refer to you as the “glue.” What is it that you do to keep everything together?

Gucci told me, “I need you to do this” [be his connection to the outside world]. And I wasn’t just mixing, I was reaching out to all of the blogs, handling PR work—I was doing everything. I was the point of contact. He called me the glue because I kept it all together. You got to stay down to keep him up. I’m on the road now actually, and I was out DJing for him for a minute. Yesterday, I was the camera man. I just fill in wherever it’s needed. I’m all for it.

How’s the TrapGod tour been?

Oh, I’ll be at Coachella [laughter]. Nah, the tour’s great—the tour’s fun. And, ya know, this is his first tour. We had a conversation the other day, and I was just like, “We got you out. That’s the only thing that matters for real. You can do what you want to do, I can do what I want to do. That’s all it’s about.” We’re friends at the end of the day.

You’ve been in the studio with plenty of great rappers. Who else do you like working with?

I love Young Thug. He’s just exciting. He’s always just switching it up. I’m working with Quavo too. Everybody that’s going now basically. We’re all family at the end of the day, being that we all came up under Gucci.

What do you think separates the great artists from the average ones, and do the great ones have common characteristics?

They have the work ethic. Everybody got their work ethic from Gucci. [The thought process is] Just go in there and rap, you know what I’m saying? Don’t come out ’til it’s done. Once it’s done, don’t even think about it—go in there an do another one. Don’t dwell on stuff. We’re all attached to it—just keep on working. And I’ve seen people work fast too. Thug works extremely fast.

Any good stories from a Young Thug recording session?

“2 Cups Stuffed”—I remember that one. That was a big song for Thug. That was one of those, everybody was about to leave the studio, and he just came in there like, “Record it.” And we did that song in 10-minutes. And then he left. He was rushing through it. And I just remember, when we first started he was like “Lean, lean—lean, lean, lean.” Then he looked at me and laughed, and he was like, “You like that?” I’m like, “Yeah, keep that.” And then after that he just kept going. But man, there are so many memorable stories though from the Brick Factory.

What are some other memorable moments for you?

I think my biggest moment that I enjoyed, was DJing at the Detroit show, because I’m from Michigan. So I got all of my family out, and they got to see me out there, turning up the whole Masonic Temple—I turned up the whole entire venue. Maybe it was the Fox? I don’t know which one it was but, you know, because I ain’t no DJ for real. But shit, you can’t tell me that the way I was going, you know what I’m saying? I was going hard. This was about three-four months ago. Yeah, that was definitely fun. I also enjoy the marketing side of the business. Like putting out his [Gucci’s] stuff. I enjoy doing that, and seeing how the fans react. And then, I don’t know, seeing some of those tapes go number one, like State vs. Radric Davis 2. I enjoyed seeing the work, because—you know that was the first tape I mixed, Corey was mixing before that. So I made that [released December ’13] all the way until he got out. I mixed, everything.

Since you’ve been so embedded in the scene, do you have an opinion on the current trap wave vs the days of T.I. or UGK?

I like them all. I mean, it’s different but—I think it’s more so that the beats are different. So rappers have to rap different. And since rappers started rapping differently on the beats—it just transformed. The Migos definitely trend-setted some shit with their pattern of rapping, and then that rubbed off on almost everyone in the industry for a minute. But I like how they came back and switched it up with the last project, Culture. They switched up their patterns, used more melodies. I like that. Overall [trap] it’s more spaced-out—more “Yeah!” and “Woo woo!”—so, it’s more spaced-out, because I don’t think people are writing as much. Everyone’s doing the punching game, so. And I fell victim to that too. When I listen back to my music, all the shit that I just punch in, I don’t really like that. Some of it’s cool, but it’s not really thought out. When I write, I like to set-up bars. You know how Freeway might say some shit, and then six bars later he’s bringing back up that little rhyming word again, you be like, “Oh that was hard.” I like shit like that.

Have you noticed a difference in Gucci’s recording sessions pre-prison and post-prison?

He doesn’t go in there and do whatever anymore, he thinks about it a little bit more. Even when he went in and did whatever though, that was hard too. But, he writes more now, and just thinks about it a little bit longer, you know? He’s trying to make hits, he’s not just trying to make music no more, he’s trying to make bangers. It’s going to take over the radio. I mean he’s on like four or five songs on the radio right now. He’s on the Chris Brown record, his single with Drake—that went number one—“Slippery” with the Migos, the 2 Chainz song. He’s just got tons of stuff that’s doing well on the radio, so that’s mainly the focus. It’s all strategic now. [We’re thinking] Let’s try to take this shit over. Ain’t no more mixtapes, put it like that. It’s all albums now.

He’s done with mixtapes for now?

Yeah, everything’s going towards the album now. Everything’s recorded is for the album.

I know you said a lot of it’s confidential, but can you give us anything about Gucci’s upcoming album, Drop Top Wizop?

Shit, nah y’all going to have to wait.

Anything else going on for you?

Yeah this year on my birthday, I’m dropping my album on July 11th. I’m also going to drop a whole bunch of videos, start my website—I’m just going to go crazy this year, man come the summertime. I’m prepping now. I’m shooting videos in the Phantom, and all that, so I’m really building at the moment. In the meantime, I’m just stacking my money by selling my verses and hooks online. I’m just doing it all. I’ve always been working, but now I’m trying to come out as an artist this year, and trying to make it happen.

Will pursuing being an artist interfere with your engineering career?

Hell nah. I can engineer with my eyes closed.