Admittedly, I’m a huge music snob. I typically refer to myself as a “hip-hop hipster”, a moniker that marks my disdain towards any rap deemed “pop” or “commercial”. I take pride in discovering artists before they gain recognition; I love putting people onto underground artists; I love artists with purpose and conviction. If a rapper is in Hot 97’s or Power 105.1’s rotation, then more often than not, they’re not on my Spotify or Soundcloud—Drake’s the exception (believe me, I know how douchy this all sounds).

So when the lyrics “I'm like hey, what's up, hello/ Seen yo pretty ass soon as you came in that door” first played through the blown out speakers in my 2005 Red Minivan (ladies, one at a time), I cringed. I searched for any artistic comprehension in Fetty’s lyrics, and all I heard was a talentless auto-tuned guy poised for a classic one-hit wonder. I immediately turned off the radio and continued to “bump” 2014 Forrest Hills Drive from my iPhone—2005 Minivans don’t come equipped with auxiliary chords.

I restricted my ears from Fetty and silently judged those who vibed with him. I thought to myself, “Ugh, those people just don’t know good music”—a similar sentiment my parents share towards me. And then the unthinkable happened: My Jewish brother and idol, Mr. Aubrey Graham, gave the New Jersey

rapper a co-sign and feature on the remix of “My Way”. I wouldn’t admit it at the time, but damn, that shit was hot. Still, I was convinced that Fetty’s rap footprint wouldn’t extend past a couple of radio hits. I mean hey, remember Chamillionaire?

2005 was a year marked by YouTube’s emergence; the start of George W’s second term; but most importantly, 2005 was the year of “Ridin Dirty”—the mantra for everyone who thought they topped the FBI’s most wanted list. Like many artists, Chamillionaire fell victim to a short, intense period of radio play, and then, silence. It can be difficult for rappers to transcend a successful single. Every successive song will undoubtedly be compared to that hit, and, fair or not, will be held to that standard. Being able to produce a catalogue of hits is a difficult feat, reserved for the best in the game. However, a library of radio jams doesn’t solidify one’s place in the music world.

Mike Jones. Who? Mike Jones. The Houston rapper might be one of the greatest marketers of all time. With little to no talent, he effectively established a place for himself in hip-hop. He garnered attention through releasing a slew of singles and music videos that blasted out his name (MIKE JONES, WHO, MIKE JONES) and phone number, to the point where we could finally stop asking “Who is Mike Jones?” But where is Mike Jones today? Fans became desensitized to his sound and persona, and his lack of talent and undiversified portfolio inhibited his career’s progression. And like many before him and many to come, he and his aura evaporated into nothingness.

Fetty’s consistent place in The Billboards Top 100 confirmed my suspicions that he was solely a radio rapper who captivated the mindless music audience; a modern day Mike Jones. My skepticism continued, but then one day while watching Sports Center and splitting a blunt with my boy, he insisted on playing “679”. I groaned at the idea, but let him throw it on.

As Blue Dream poured out my nose, Fetty poured in my ears. I don’t know if the weed was inhibiting my judgment, but fuck that song is sonically pleasing. I tried to stop my head from bobbing back and forth, but I couldn’t prevent the involuntary action—my body was speaking to me, and it said “quit fighting the Remy Boyz.” As the blunt neared its roach, I began to panic and had a paranoid inner monologue: “Shit, do I like Fetty Wap?” … “Will my hip-hop head contemporaries judge me?” … “Am I everything that I hate?” But I had to maintain appearances as an exclusive intelligent rap fan. Despite all the evidence that I was warming up to Fetty, I refused to accept him into my artist circle. I compensated by only listening to alternative, very underground rap that I didn’t even enjoy; I was just trying to prove a point.

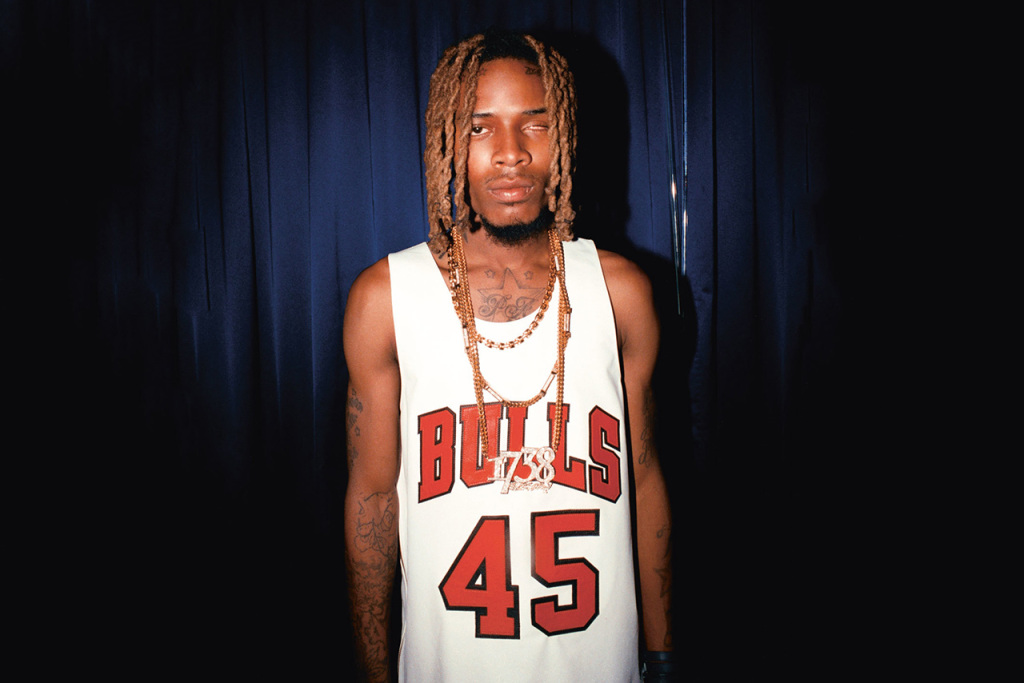

I got a text from a buddy one night who shares the “hip-hop hipster” mentality saying, “Baby girl you so damn fine doe, I’m tryna know if I can hit it from behind doe”. At first, I was in shock that he texted me these lyrics—not because I thought he actually wanted to “hit me from behind doe”, but because he too was listening to the 1738 rapper. I felt relieved. He validated my new affinity for the one-eyed rapper—clearly, I’m not insecure. And then, I took the plunge.

I got in to work early. I looked all around to make sure no one was watching. With my hands shaking and a bead of sweat hugging my temple, I typed “Fetty Wap” into Spotify. I pressed play on his new deluxe album, and waited. My worries were confirmed and five words that I never thought I would say slipped out of my mouth: “I fucks with Fetty Wap.”

My blinders were lifted. I could begin to appreciate him as an artist—it still feels weird to say. I began to respect him for who he is—a hard working individual strongly establishing a presence in a very oversaturated hip-hop market. I began to take notice that other artists sought him out for collaborations due to his brand power, visibility and musical ability. I began to take pride in my fellow New Jersey native. I began to abandon my preconceived notions that if something is commercially viable, then it can’t be good.

I’m not saying that Fetty is perfect. Believe me, there’s room to improve. He still hides behind an auto-tuned mask and the majority of his content revolves around shallow concepts like glocks and bitches. But the guy’s consistently putting out hits, and that, in and of itself, is impressive. While his content isn’t game changing, he’s connecting with his fans and they’re hungry for more. I’m curious to see his reign continue, and I’ll admit I’m quietly rooting for him. But in order to evolve and grow as an artist, he needs to break out of his creative risk encrusted shell. He isn’t pushing boundaries and he isn’t breaking ground. Those who make it, I mean really make it, aren’t afraid to push themselves and step outside their comfort zones.

Kanye West wouldn’t be the international superstar that he is today if he was afraid of risk or critics’ opinions—clearly for the latter. But he had a vision and standard for himself, and he knew achieving them would require risk. I didn’t think Yeezus was great, but I respected it so much because it differentiated his portfolio and pushed boundaries. Rick Ross recently remixed Adelle’s megahit, “Hello”, by adding his own verse and flavor to the track. Most wouldn’t group Adelle with hip-hop, but Rozay seamlessly and effectively injected his presence into her deep, soulful track. It’s obvious why these artists have enjoyed longevity and popularity—they break the mold and they take risks.

It’s too soon to tell if Fetty’s walking the same path as Mike Jones, or if he’s going in a different direction like Kanye or The Boss (not that boss). While it’s true that history repeats itself, that doesn’t have to be the case for Fetty. He needs to start taking risks. He needs to hone his craft. This adopted rapper mentality that quantity trumps quality is bullshit and needs to be expunged immediately. Kendrick and J. Cole are prime examples of artists who take their time perfecting every song, down to each bar and musical note. It’s their livelihood—anything less than their best is simply unacceptable.

I criticize Fetty because I care about his career development. I’d like to see him beat the odds and remain relevant in today’s competitive rap landscape. Despite the shortcomings I’ve illuminated, it’s important to recognize the accolades Fetty’s achieved in a tight time frame: Numerous top billboard hits, a well-received album and presence. But complacency is the enemy of greatness. He needs to charge forward into the abyss of uncertainty and create something outside his comfort zone. People will forget Chamillionaire. People will remember Kanye.