Imagine a little boy growing up in the ‘90s, who idolizes rappers. Let’s call him Jarred. Everything Jarred does is an homage to these larger than life figures: the clothes he wears; the slang he speaks; the attitude he conveys. Everything is within their image. Everything is to make them proud. Imagine he’s 10-years-old—a very impressionable, confusing age.

As his Hip Hop consumption increases, so does Jarred’s cultural absorption. He’s now walking with a little swag; he’s able to recite Biggie lines on the spot (even the most obscure ones); he’s wondering how he can hit a lick. But the more Jarred tries to resemble his idols, the more aware he becomes of one eluding facet. No matter how hard he tries, he’s a square trying to fit into a circle. He suppresses these feelings, despite their deafening reality.

Jarred comes home from school one day. He eats a snack, watches some TV, and then retreats to his bedroom—his Hip Hop sanctuary. He lies on the carpet, hands cupped behind his head, and stares at the gods hanging from his wall: 2pac, Big Daddy Kane, Snoop, Nas. After finishing praying to these gods, he stands up, wipes the dust off his velour sweatpants, straightens out his chain, and looks in the mirror. The superficial similarities with his Hip Hop deities are becoming uncanny. But still, deep down, Jarred’s aware of an instrumental difference. That deafening reality is growing louder.

It’s a Tuesday—one of his dad’s days to drive him to school. Hot 97 is commonplace in his car. Waiting in traffic, 2Pac’s “I Get Around” comes on the radio. Jarred initially starts nodding his head in unison with the beat, adding a snap every so often. But then, he starts listening to the lyrics closer. It’s clear that Pac is bragging about his numerous sexual conquests. His forehead begins to sweat. He’s no longer bobbing his head to the beat, and the hands that were snapping are now blocking the profuse sweat gushing from underneath his Starter cap.

He rushes into school, barely saying goodbye to his father. Avoiding people like Herschel Walker on the football field, Jarred makes it into the bathroom. Cold water splashes on his face; temporary relief ensues. He then looks in the mirror, unable to shake what just happened in the car. Jarred does a security clearance of the bathroom—he’s alone. He audibly exhales, and whispers to himself, “Why don’t I feel the way 2Pac does about girls? Why can’t I think that way? Is there something wrong with me?”

As the day continues, Jarred’s mindset remains fixated. It’s 2:45pm. His father is waiting outside school, ready to take him home. Hot 97 still plays in the car. Brand Nubian’s “Punks Jump Up To Get Beat Down” comes out of the staticky speakers; one line grabs Jarred’s attention, “Though I can freak, fly, floow, fuck up a faggot / Don’t understand their ways I ain't down with gays.” A tear streams down Jarred’s cheek. The deafening reality can no longer be suppressed: Jarred knows that he’s gay, and he knows that the majority of his ‘90s Hip Hop idols don’t approve of his orientation. He’s crushed; estranged; alone.

Hip Hop has historically been outwardly homophobic. The community has viewed it as weakness, a disease, and an odd trait that makes you inherently different, worse. As both an avid Hip Hop fan and proud supporter of the LGBT community, this was always an issue that I reproached. The shallow, scared thinking is more ironic than anything, considering that a large portion of rap music is protesting racism, and yet they’re calling gays weird, different, and inferior. But given recent events, I think Hip Hop’s homophobia might finally be shifting towards a progressive attitude. I think it might finally be safe for a young, openly gay child to comfortably be a Hip Hop fan.

Let’s imagine a 10-year-old boy growing up in the 2010s. We’ll call him Aaron. Like Jarred, Aaron is a proud, vocal Hip Hop advocate. It’s in his DNA, and manifests in his daily life: he wears a plain dad hat; his Stüssy crew neck sweatshirt slightly billows, yet adheres to his thinner stature; his slim, slightly ripped black jeans stop just shy of his Yeezy tongues.

Aaron’s favorite artists are Kanye West, Chance The Rapper, and Frank Ocean. He’s obsessed with their soulful artistry, colorful production, and innovation—they’re unafraid to be themselves. They resonate with him, helping Aaron traverse life’s rocky terrain. “Hey Mama” played on repeat after his friend’s mother passed; he exhausted 10 Day after getting suspended from school for cheating on a math test; “Forest Gump” gave him the courage to come out to his parents.

Rehearsing his coming out speech endlessly, Aaron still requires more encouragement to break the news to his parents. Unsure of what his friends would think, Aaron turns to his real best friend: Hip Hop. Just like it had been in the past, Hip Hop would prove to be Aaron’s greatest confidant, his greatest supporter. It nudges him towards his parents’ bedroom door, and gives him the confidence to knock twice.

In their nightwear, Aaron’s parents crack open the door, welcoming in their 10-year-old son. He’s visibly distraught. Sitting on the edge of their bed, fumbling with his thumbs, muttering a few words under his breath to get him started like someone trying to turn on an old car in the middle of winter, Aaron looks back over his shoulder towards the doorway, questioning his decision. Suddenly, Hip Hop’s comforting presence washes over him. He think about those brave trail blazers.

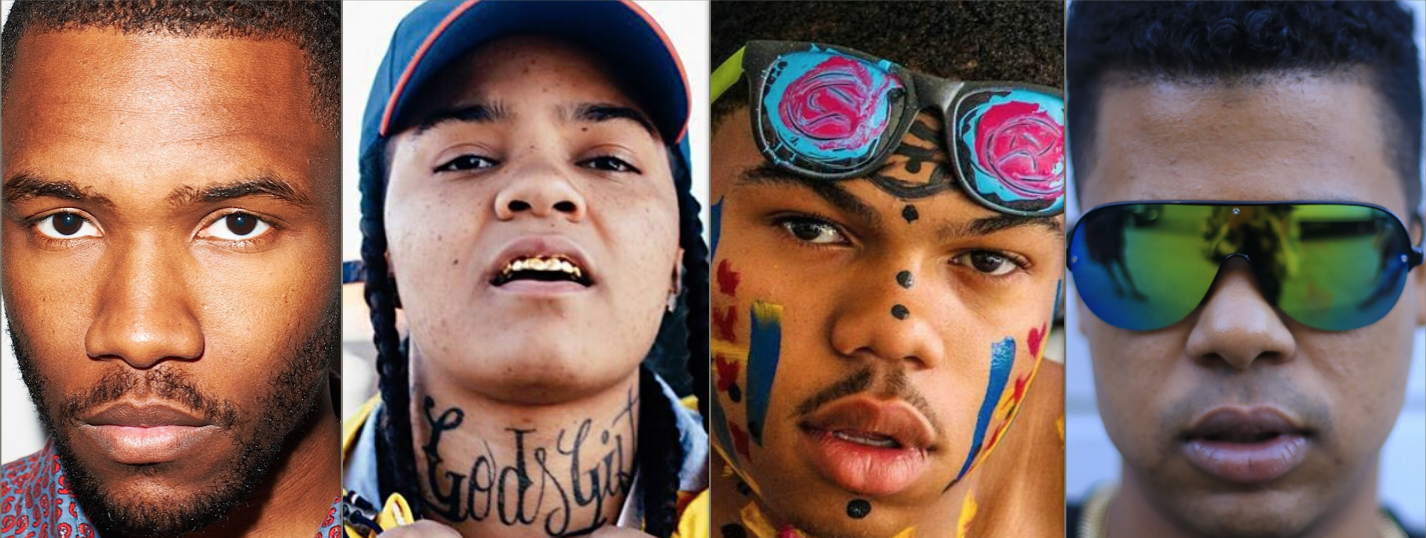

Frank Ocean is a pioneer in Hip Hop’s gay community by being one of the first big names to come out as a bisexual (2012). As a part of the Odd Future collective—a seemingly homophobic entity based on their lyrics—it was unclear how his homosexuality would be received. Group leader, Tyler The Creator, and frequent employer of homophobic slurs, welcomed Frank’s announcement with open arms; in fact, he was one of the first people Ocean told. He even made light of Frank’s situation by saying, “I kinda knew, because he likes Pop Tarts without frosting on them, so I knew something was weird. [Laughs] But that's my nigga.” Brooklyn’s quickly rising star, Young MA, has known that she’s a lesbian since her childhood. While she’s proudly gay, she doesn’t want to be labeled as the “LGBT rapper”—she wants her talent to be her most interesting factor. Last week, Chance The Rapper’s brother, Taylor Bennett, came out as a bisexual a day prior to his 21st birthday in a series of tweets, saying that he wanted to be truer to himself, and help those struggling with the same issues. Shortly after Bennett’s announcement, Atlanta’s iLoveMakonnen also came out via Twitter to a supportive audience.

Aaron recalls these fearless individuals, and channels their valiant announcements into his own. He let’s out an audible exhale, collects his thoughts, and reveals the news to his parents. As soon as the words leave his mouth, he starts sweating profusely; shaking uncontrollably; fearing his parents’ reaction. They look at Aaron, then at each other, and back at Aaron with warm smiles.

Hip Hop has made incredible strides since the ‘90s and ‘00s in regards to accepting homosexuality. It’s beautiful to witness this genre progress. From “Though I can freak, fly, floow, fuck up a faggot / Don’t understand their ways I ain't down with gays” to two rappers coming out in the same week is nothing short of incredible. It validates my Hip Hop pride, and nullifies outdated claims that Hip Hop and homophobia are synonymous. Yes, the problem is by no means eradicated from rap, but its important to commend these positive steps, and acknowledge Hip Hop’s accepting direction. While these juxtaposing stories are hypothetical anecdotes, their reasoning holds true: being a gay ‘90s Hip Hop lover was strikingly worse than growing up a homosexual rap fan today. The same genre that made Jarred feel insecure and ashamed helped Aaron come out of the closet. This increase in homosexuality tolerance is exactly what our country needs right now.

In an uncertain American political climate, headed by a bigoted charlatan with small hands, it’s consoling knowing that progression is materializing in unconventional forms. When we look around and feel hopeless, let’s remember the progression of certain cultures. Let’s take solace in that. Frank Ocean likes Pop Tarts without frosting, and Hip Hop is embracing the LGBT community.